Speaker Advocates Avian Conservation

SPC Programs & Events October 27, 2015By Nate Lovely

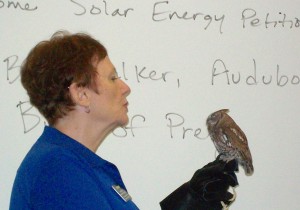

“These birds, by definition, catch their food with their feet,” explained former professor Barbara Walker during her presentation on birds of prey on Wed, Oct. 14 at St. Petersburg College in Tarpon Springs. Many students attended this lecture to learn about these birds, sometimes referred to as raptors.

Walker proceeded to explain, “Birds of prey are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.” This law, first enacted in 1916, “makes it illegal for anyone to take, possess, import, export, transport, sell, purchase, barter, or offer for sale, purchase, or barter, any migratory bird, or the parts, nests, or eggs of such a bird except under the terms of a valid permit issued pursuant to Federal regulations” Some continue to disregard this treaty. Walker took it upon herself to educate her audience about the birds at risk.

She began by providing facts about each bird of prey. For example, the bald eagle, whose lifespan averages 20 years in the wild, reaches maturity at 5 years of age, and some birds of prey migrate as far north as Nova Scotia, leaving parks in the U.S. devoid of raptors during the summer. While birds of prey mate for life, they can change mates in the event one passes away.

Walker pointed out, “Reverse sexual dimorphism is predominant in birds of prey.” In other words, the females tend to be bigger than the males. And while birds can perceive motion and detail 2-3 times better than humans, “owls locate primarily by hearing.” Walker asked the audience if they knew what animal makes up most of the screech owl’s diet as her assistant took a screech owl out of its cage to show the room. While many students guessed small rodents like mice, the screech owl actually feeds mostly on cockroaches. Some Pinellas county residents might be relieved to learn they live in “the screech owl capital of North America.”

Walker then explained the dangers these birds face. The osprey’s diet is almost exclusively fish; however, algal blooms make fish hard to see. This makes it difficult for juvenile ospreys to hunt. Construction site waste can also prove hazardous to ospreys. Caution tape, for instance, can entangle their legs. If an osprey struggles enough, it can dismember itself while trying to escape. And the highest rate of mortality for owls, much to the surprise of the audience, “is being hit by cars,” though not every encounter with a car proves fatal. Before drawing the presentation to a close, Walker’s assistant took another owl out of its cage, this one much smaller than the last one. The owl’s name was Patch. He’d survived being struck by a car, but the hit caused him to lose an eye. Patch appeared coy, reluctant to face the audience, and was put back in his cage shortly thereafter.

Walker then explained the dangers these birds face. The osprey’s diet is almost exclusively fish; however, algal blooms make fish hard to see. This makes it difficult for juvenile ospreys to hunt. Construction site waste can also prove hazardous to ospreys. Caution tape, for instance, can entangle their legs. If an osprey struggles enough, it can dismember itself while trying to escape. And the highest rate of mortality for owls, much to the surprise of the audience, “is being hit by cars,” though not every encounter with a car proves fatal. Before drawing the presentation to a close, Walker’s assistant took another owl out of its cage, this one much smaller than the last one. The owl’s name was Patch. He’d survived being struck by a car, but the hit caused him to lose an eye. Patch appeared coy, reluctant to face the audience, and was put back in his cage shortly thereafter.

Walker concluded her presentation by asking the audience, “What, in this room, is most capable of protecting birds of prey?” The answer – the audience themselves. Walker encouraged students to volunteer to help raptors. There are many opportunities available in Pinellas county. Boyd Hill Nature Preserve in St. Petersburg, for example, is seeking volunteers to help birds of prey and animal care interns. Moccasin Lake in Clearwater also provides opportunities to help these birds. Students interested in volunteering can fill out an application online at StPeteParksRec.org or MyClearwater.com.

Walker concluded her presentation by asking the audience, “What, in this room, is most capable of protecting birds of prey?” The answer – the audience themselves. Walker encouraged students to volunteer to help raptors. There are many opportunities available in Pinellas county. Boyd Hill Nature Preserve in St. Petersburg, for example, is seeking volunteers to help birds of prey and animal care interns. Moccasin Lake in Clearwater also provides opportunities to help these birds. Students interested in volunteering can fill out an application online at StPeteParksRec.org or MyClearwater.com.

To attend more events like this one, join the Environmental club, which has a full list of programs available.

Header photo from Sarah Bailey (flickr creative commons license).