Nine’s The Key Number for Greenlight Pinellas

News & Politics October 26, 2014by Jim Dietrich

Lost in all the talking points and rhetoric about why one should or should not vote for Greenlight Pinellas is a number: nine.

But what does it signify? Is it how many trains will be running at any given moment, the amount of added bus routes to the system, or the amount of people projected to ride the buses? Actually, it’s none of the above.

It is the amount of dollars the average lower-income resident will spend extra in sales tax to receive increased transit options.

Confused? Here’s a primer:

Greenlight Pinellas is the plan up for vote next week that will remove a decades-old property tax add-on called an ad valorem that has subsidized the PSTA transit system; currently, that ad valorem sits at 7.5 mills, or 0.0075 percent, bringing in roughly $60 million in funding for 2013. That sounds like a lot until you realize the operating costs far exceed that, meaning PSTA is running in the red—and they’re almost completely broke.

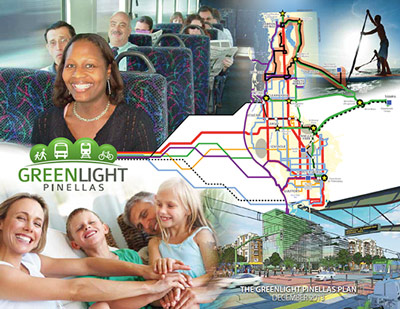

Instead, a new one-percent sales tax will be added to the current seven percent Pinellas County sales tax starting in January 2016 to make up for it, bringing the tax to eight percent. This is projected to boost funding to PSTA by up to 400, and for that extra money the county would get increased bus service, expanded routes to Tampa and Pasco County, and even a light rail that would run from Downtown St. Petersburg to Downtown Clearwater, stopping in Carillon and Largo along the way; this train is scheduled to be open in 2021.

There have been numerous points by both sides why we should vote one way or another, but one point in particular really hits home for the lower-income residents, students included. Leader of the main anti-Greenlight group No Tax for Tracks, Barbara Haselden, on numerous occasions has raised the specter of this swapping from property tax to sales tax as “regressive” and “disproportionately affecting the poor.”

This argument does make sense on paper. Those with less money to spend would have to put out even more money to buy goods and services they need, thereby moving the burden from the land-owner (presumed to be “rich” for this argument) to the backs of the poor. In fact, simple math says a minimum wage worker that makes about $17,000 a year would pay an extra $170 in a one-percent tax hike…or does it?

In reality, the burden on everyone, not just the poor, isn’t increased by a factor of one percent of a person’s entire income. For starters, this is only a sales tax increase, not an income tax. Since the vast majority of people pay for some sort of utility, rent, or a mortgage, that portion of the income is not affected; those items do not have a sales tax attached. Neither do medications, medical supplies, medical visits, first-aid items, unprepared food, water, most baked goods, baby food, flags, religious texts, most fertilizer, and most seeds.

Now, assume that about 30 to 40 percent of someone’s minimum wage income is devoted to non-taxable items, like food, housing, and utilities. That leaves roughly 65 percent, or about $11,000, of their remaining income going toward sales taxable items (for ease in math, I’m ignoring the obvious federal income tax that wouldn’t be spendable). That brings the new increased tax burden to $110. Divide that by 12 months and, voila!, about $9 a month appears.

Why is this so important? The crux of the argument No Tax for Tracks provides for the poor is that mindset of “you will pay more.” Sure, the poor will, but for an extra $9 a month, that can mean the difference between walking to the local McDonalds for minimum wage and having a bus actually service their area to take them to higher-paying work, thus getting them out of the “poor” category. This means more economic empowerment. This means freedom for the oppressed.

Sure, that sounds like a lofty ideal, but the truth of the matter is that if the vote favors the “no” crowd on Tuesday, that freedom will surely disappear, as PSTA has already announced up to a 30 percent reduction in service to prevent insolvency as early as this coming January. That will hurt the poor a lot more than $9 a month.

Nine dollars doesn’t seem like a lot to most people. Heck, that’s what some will spend on a singular meal at McDonalds. However, the person behind that McDonalds counter sees the same $9 as either a ticket to bigger and better things, or a ball-and-chain of poverty they can seemingly never escape.

Remember this at the polls.